Tintin Crosses The Atlantic: The Golden Press Affair

- Image © Hergé/Moulinsart

In 1958 Georges Duplaix wrote to Casterman to express his interest in publishing Tintin in the USA. At the time, the dust was still settling after the ‘horror comics debate’. There had been articles condemning comic books since the Forties, and a New York Senate panel had actually banned them in 1955. Comics had been described as debased and semi-literate, and were accused of keeping children from reading ‘proper’ books. This was probably not the best environment in which to try to launch a major work of the comic-book tradition. However, Tintin appeared to have a good, clean image, and he was becoming more and more popular in Europe, so why not America?

Duplaix had a considerable reputation in publishing. In 1941, as head of the Artists and Writers Guild, the Frenchman had been overseeing the development of new children’s books when he conceived of Little Golden Books: small, colourful picture books, modestly priced, durable and designed to be handled by kids. They were just 25 cents each, a remarkably low price at a time when most children’s books cost two or three dollars, a luxury for most American families. Little Golden Books proved to be an immense success and helped turn parent company Western Printing into America’s largest children’s book publisher.

Duplaix’s letter asking for permission to publish Tintin in the USA was passed to Pierre Servais, rights manager at Casterman in Tournai, Belgium. Servais sent English and French editions of some of the books to New York, and suggested they release the titles in the same order as the London-based publisher Methuen had done in the UK. In 1958 Methuen had just released their first two Tintin titles, The Crab With the Golden Claws and King Ottokar’s Sceptre, with The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure in the pipeline. Despite some initial resistance from libraries, the series was an early success in Britain, enjoying a front-page review in The Times Literary Supplement, which hailed them as “works of high quality and even beauty” and “brimming over with intelligence and life”.

The US series was to be published by Golden Press, a company set up in November 1958 and jointly owned by Western Printing and Lithographic Co. and Affiliated Publishers Inc. The company president was Albert R. Leventhal, who had taken over as head of the Artists and Writers Guild from Duplaix. Golden Press mainly handled lines acquired from Simon & Schuster: large picture-book nature guides and encyclopædias – educational books. They would also publish Tintin, a sign that they wanted to elevate the albums above the status of ordinary comic books. Duplaix continued to negotiate with Casterman on Golden Press’s behalf and arranged for the text to be translated from scratch in an American idiom.

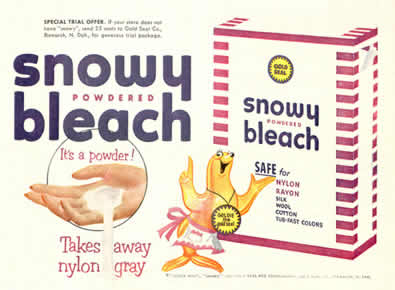

The contract between Casterman and Golden Press stipulated that the latter publisher could choose their own names for the characters in the books, but must keep them as close as possible to the originals. Golden Press decided that the main characters, Tintin, Captain Haddock, Thompson & Thomson and Calculus, would take the same names as in the British editions, but that Snowy was to be called “Buddy”. Duplaix felt the name Snowy would sound ridiculous to an American ear, especially because it had been the brand name for a powdered bleach in the USA. Servais, however, was not happy about this change; he preferred the name Snowy, as used in the Methuen editions. More importantly, so did the Hollywood company that was planning to produce animated cartoons of Tintin. Servais was concerned that different names might cause confusion when the cartoons were shown on American TV. After some head-scratching at Golden Press, Duplaix wrote back to say that they had finally decided to aband on the name Buddy and use Snowy instead.

- A 1950s magazine advertisement for Snowy powdered bleach

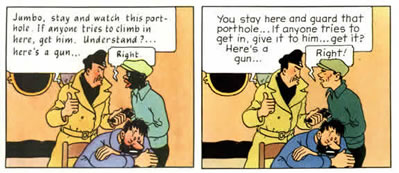

Before the translations began in earnest, Hergé agreed to redraw several panels for The Crab with the Golden Claws depicting black characters. The US censors didn’t approve of mixing races in children’s books, so the artist created new frames, replacing black deckhand Jumbo with another character, possibly of Puerto-Rican origin. Elsewhere, a black character shown whipping Captain Haddock was replaced by someone of North African appearance.

- The original Jumbo as he appeared in the first Methuen edition of The Crab with the Golden Claws in 1958 (left) and his replacement made at the request of Golden Press (right).

- Image © Hergé/Moulinsart

It was Georges Duplaix’s daughter who worked on the translation of the first book, King Ottokar’s Scepter. “I was 16 at the time and a great fan of Tintin – I still am. It was my very first paid translation assignment and I loved every minute of it,” remembers Nicole Duplaix, a successful photographer, writer and zoologist for more than 20 years.

In 1959 Golden Press began translation of the next three titles: The Crab with the Golden Claws, The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure. This time they hired Danièle Gorlin (now Gorlin Lassner), the daughter of the Duplaix children’s private French teacher (note that her name is spelled incorrectly – as Danielle – in the first three books she translated). The children often asked Danièle to translate expressions for them, and seeing her skills, they asked if she’d be interested in translating Tintin, then put her in touch with their father. “I agreed to, I think it was under $200 a book, with no additional rights to anything, which was fine. I was going to graduate school the next year and, for me at that time, it was very nice additional money,” recalls Danièle, who is now the Dean of Admissions and Coordinator of Foreign Languages at the Ramaz School in New York.

Across the Atlantic, the English translators Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner had established what grew to be a close relationship with Pierre Servais, and later Hergé himself, allowing them the rare privilege of being able to ask for help in perfecting their translations. It was different in the United States. “I had absolutely no contact with Hergé,” remembers Danièle, “although, of course, I was aware of the popularity of Tintin in France and Belgium. I really went along just talking to myself – just conscious that it should be in the idiom of the land.”

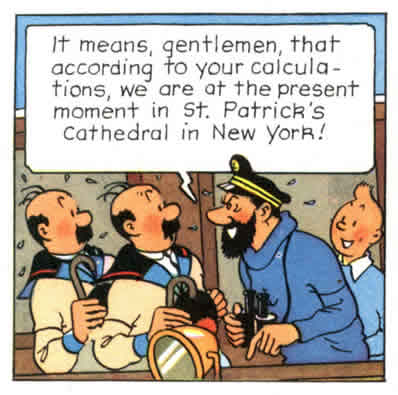

“I found the humorous parts are always the challenge, and also some of the technical parts,” she adds. “I had no idea what type size they were going to use, so I was very conscious of the balloon – that the text should fit into it, and of trying really to make it as American as possible to myself.” Consequently, the Golden Press editions include some interesting differences to their counterparts in other languages. For example, on page 23 of Danièle’s translation of Red Rackham’s Treasure, Thomson and Thompson mistakenly calculate their position to be in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, as opposed to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (as in the French original) or Westminster Abbey in London (as in the Lonsdale-Cooper/Turner translation).

Despite the unfortunate mis-spelling of her name, which she describes as “a life-long battle”, Danièle still retains fond memories. “I loved doing it,” she says, “it was great fun. I loved the characters – I even started dreaming little bits of Red Rackham – absolutely marvellous!”

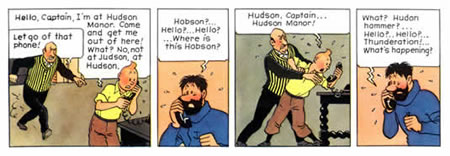

- Hudson Manor

- Image © Hergé/Moulinsart

Whilst the translation of The Crab with the Golden Claws was in progress, another problem was noticed, and Duplaix wrote to Casterman to explain: “The Crab with the Golden Claws … is a very entertaining story, but people drink with great delight, beer, champagne, rum, whisky, etc. – in a word, they drink enormously. If we publish this story as it currently is, we will encounter an extremely sharp opposition from critics and the teaching profession. This could do serious harm to the launch of the series.” The solution they had found was to tone down the text slightly, and, when confronted with illustrations of the captain drinking straight from the bottle “with an excessive enthusiasm – for example, pages 14, 16, 19, 36”, to simply remove them, the empty frame to be filled with some text. “I am sure you understand that an American, very often puritan, point of view is different from the European point of view. A joke that everyone would accept with a smile in France or Belgium would horrify people here. The presentation of alcoholism, especially in a humorous form, is absolutely taboo.”

These concerns were passed on to Hergé, who drew just three new frames for pages 19 and 25 of the book to replace offending ones. With this gesture, he carefully avoided what might have become a mammoth undertaking. The changes the artist made, however, remained in all future editions of the book worldwide.

The first Methuen edition (left) included this frame from page 25 of The Crab with the Golden Claws, whilst the Golden Press edition kept only the text (centre), before Hergé redrew it, shown here from a later Methuen edition (right).

- Image © Hergé/Moulinsart

Around a year after Duplaix’s original letter to Casterman, the first four books were released simultaneously, and advertisements for them appeared in The New York Times in the run-up to Christmas. “Except for a hug, a kiss, and a college education, you can scarcely give your children anything that they and you will find more worthwhile,” proclaimed one advertisement, urging parents to put a set of the books under the Christmas tree. “You will be a hero,” it ran. “Not so big a hero as Tintin perhaps, but to rival him you would have to give the children nothing less than a live foreign agent, bound and gagged. We have no idea where you can get one of those; the books, however, are on sale at all bookstores.” Even the Belgian Consulate in New York helped drum up some publicity by arranging for the Belgian airline Sabena to have copies of the books on all their flights between New York and Brussels. Golden Press also held discussions with Life magazine about a possible feature story on Tintin and Hergé. The idea was to show photos of world-famous Tintin fans (Madame Chiang Kai-shek, Brigitte Bardot and others) and pictures of various Tintin products (soap, perfume, etc). In addition, Golden Press met with Larry Harmon and Jacques Grinieff to view some of the Hollywood-produced cartoons, and to discuss a joint publicity campaign. The US publishers were very impressed with the animations and must have felt that their broadcast would help to make Tintin a household name.

The new year came in and the sales results were disappointing. Golden Press had sold around 8,000 copies of each title over the Christmas period. A Newsweek book review from February 1960 praised the series, but made no attempt to hide the disappointment felt at Golden Press. “With high hopes for the Christmas trade,” it ran, “the Golden Press publishing house brought out the first four Tintin books here last fall at $1.95 each – and watched their fate with dismay. Although Europe buys Tintin at the rate of 250,000 copies a week, the boy conqueror fell flat in front of an American public which understandably distrusts anything with the look of a comic book. Preparing last week to try again soon with a pair of new Tintin adventures called Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon, Albert R. Leventhal, president of Golden Press, drew out a sigh. ‘This country,’ he said, ‘is behind in the missile race and it’s behind in the Tintin race.’”

“I have the feeling that Golden Press wanted it to sell immediately,” says Danièle. “It didn’t – it takes time. I don’t know if they gave it the ‘oomph’ it needed.” The planned Life article was cancelled for the time being, and the two new books, Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon, were released with little fanfare. “Americans could not understand why they had to pay so much for a comic book” adds Nicole Duplaix as another reason for the failure. And that resemblance to a comic book obviously hurt. “In spite of the good reviews, we have been unable to overcome this prejudice,” wrote Golden Press in April 1960, explaining the poor sales figures to Servais.

Golden Press produced no more Tintin books, although the agreement had been to do at least another two titles. By 1962 Servais was so disappointed by the publisher’s lack of interest that he asked for the rights back. Leventhal replied that if no other publisher was interested, and because there was a chance that Tintin would break into TV via the cartoons, they would like to hold on to the rights “and try again to help popularize in the United States this wonderful young man.” However, Methuen were given clearance to sell titles in the USA that Golden Press did not issue. When the contract with Golden Press expired in the middle of the decade, Casterman began looking for another American publisher.

By 1971 Tintin’s popularity had greatly increased in the USA, chiefly because of the serialization of the adventures in Children’s Digest. These had begun in 1966, using the British Lonsdale-Cooper/Turner translations, and had a circulation of around 700,000 copies monthly. The Larry Harmon–Belvision cartoons were also syndicated in the USA at around the same time. When Hergé visited the country for the first time that summer to undergo medical treatment, followed by a six-week tour of the North American continent, he was struck by the popularity of Tintin among American children.

The comic-book genre in general had undergone a renaissance in the USA since the mid-1960s and was now being taken seriously, the horror comic debate well and truly put to rest. As Casterman had still not found another publisher in the country, Servais re-established contact with his former associates from across the Atlantic, now known as Western Publishing. He told them not to be scared by their initial lack of success: a Stockholm firm had published four Tintin books eight years previously and had given up after the results proved unsatisfactory. Another publisher then took the books in 1969 and was selling 1,000 copies per day. Western Publishing were aware of this, as the Danish publisher Per Carlsen had already told them of his fabulous success with Tintin in Sweden, Denmark and Germany, and their mouths were beginning to water. A reappraisal of the series was needed.

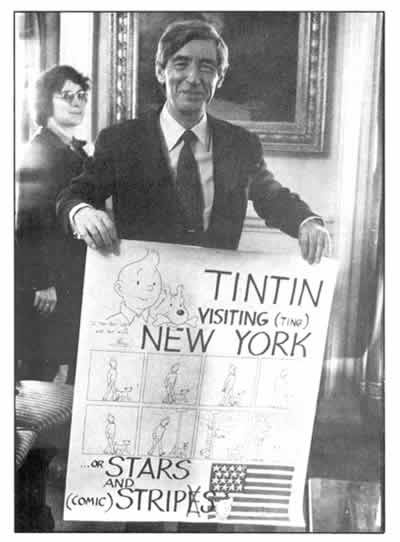

Servais thought it would be good to sign a new contract before the beginning of a convention of European comic strips to be held in New York in April 1972 at the Royal Manhattan Hotel, to which Hergé was invited as guest of honour. Servais wanted to be able to tell everybody at the convention that Western Publishing were to launch the new US edition of Tintin. However, although the convention was a great success, Hergé having presented the Mayor of New York, John Lindsay, with a large strip he had especially drawn, the signing of the contract had not taken place.

Hergé at a convention of European comic strips held in New York in 1972 with the strip he presented to Mayor John Lindsay.

- Image © Hergé/Moulinsart

Western Publishing had been considering re-launching the series under a new contract, which stipulated the use of the Lonsdale-Cooper/Turner translations, but after “extensive research”, they finally decided not to. Servais wrote one last time, saying he was “a bit disappointed”, and wanted to know just one thing: was it a matter of price? In other words, were the books too expensive or was there no market for them? Western’s response was that in their experience as one of the largest American comic-book publishers, a hardcover juvenile comic book simply would not sell in the US market. They felt that to an overwhelming majority of their readers, a comic book was something that “one can purchase for 20 cents or less anywhere in America”. The case was closed, as far as Western were concerned.

Tintin's American fans didn't have to wait too long to see their hero in print again. In 1974, the publisher Atlantic-Little, Brown began to issue the series, this time using the unaltered Lonsdale-Cooper/Turner translations. The books are still available today and Tintin maintains a small, yet significant, cult audience within the USA. Golden Books Family Entertainment, Inc., the successor company to Western Publishing, went bankrupt in 2001. The publishing company Random House acquired the assets and now controls Golden Books’ publishing operations; Duplaix’s evergreen Little Golden Books are still being produced.

America didn't really get off the starting blocks in the “Tintin race” and European comics are still largely alien to an American audience more used to their own brand of the tradition. However, with Tintin fan Steven Spielberg currently making plans for a Tintin movie, things could very soon change.

Collecting the Golden Press editions

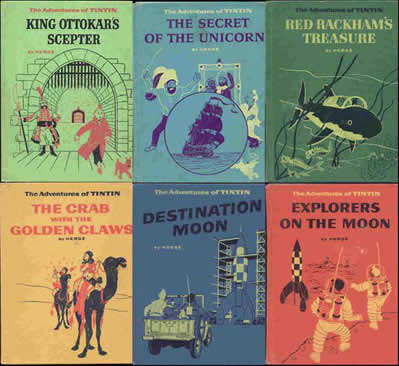

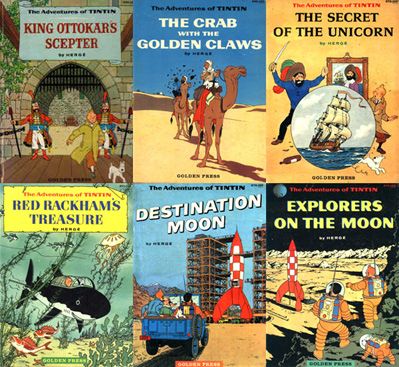

- The covers to the Goldencraft Library Bound editions

The first four books issued in 1959 sold around 10,000 copies each in total, and although sales figures for the following two books issued in 1960 are not available, they would probably be considerably lower, theoretically making those books scarcer. However, it's unclear how many were printed and whether unsold copies were pulped or just ended up in the bargain bins. The unique translations make them desirable to collectors, although finding a mint condition copy of a Golden Press edition could prove to be elusive and the varying prices often paid at Internet auctions make their true value difficult to determine.

The Golden Press editions were the first Tintin books to receive printed spines—a cloth-tape spine had been used by Casterman and Methuen until 1963—and unlike the Methuen editions, which were printed by Casterman in Belgium, these were printed in-house by the Western Printing and Lithographing Company in Racine, Wisconsin. The prototype spines have proved to be rather delicate and are commonly found damaged or missing altogether.

- The covers to the Golden Press edition Tintin books

Steve Santi's Collecting Little Golden Books values the standard Golden Press editions at US$125 (roughly £70) each, which would be a fair price in mint condition. Even harder to find are the Goldencraft Library Bound editions made for use in schools and libraries, which have a cloth material, Arrestox, stitched over the covers for durability. These could fetch $200+ in mint condition.

Acknowledgements

With special thanks to Etienne Pollet at Casterman, Danièle Gorlin Lassner, Nicole Duplaix, Martina Habeck, Pascal Thivillon, Simon Doyle, Steve Santi and Cyrus K Rustamji.

Bibliography

King Ottokar’s Scepter(Golden Press, 1959) translated by Nicole Duplaix

The Crab with the Golden Claws (Golden Press, 1959) translated by Danièle Gorlin

The Secret of the Unicorn (Golden Press, 1959) translated by Danièle Gorlin

Red Rackham’s Treasure (Golden Press, 1959) translated by Danièle Gorlin

Destination Moon (Golden Press, 1960) translated by Danièle Gorlin

Explorers on the Moon (Golden Press, 1960) translated by Danièle Gorlin

Collecting Little Golden Books (Krause Publications, 5th edition 2003) by Steve Santi

Hergé et Tintin Reporters (Editions du Lombard, 1986) by Philippe Goddin

Tintin The Complete Companion (John Murray, 2001) by Michael Farr

‘Tintin crosses the channel’, The Times Literary Supplement, 5 Dec 1958

‘Here’s a good comic’, Newsweek, 22 Feb 1960

‘America Discovers Tintin’, The Comics Journal Nº 86, Nov 1983

Text © 2007 Chris Owens. Used by permission. Images (except for the Snowy bleach advertisements) © Hergé/Moulinsart/Casterman/Golden Press.

More

- Guides: Tintin Books

- Guides: First publication dates of The Adventures of Tintin

- Articles: More articles by Chris Owens